|

The Star, May 24, 1999

Killer unmaskedCaught in the viral spiralBy Meng Yew ChoongWHAT was the virus that killed over 30 children in Sarawak two years ago? Chances are, most people will say it was coxsackie. Wrong answer. Because coxsackie, which was declared the culprit at the height of the deaths, was found in the end NOT to be the virus responsible. Till today, scientists have yet to ascertain the real killer bug.

It would appear that a name that is bandied too often remains etched in the mind, as evident in the present pig-related viral outbreak that was attributed to the Japanese encephalitis (JE) virus which is spread by the Culex mosquito. When pig farmers and farm workers in Ipoh started dying last year, JE was suspected. In November, the health authorities declared that JE was the virus behind the spate of "mysterious" deaths in the pig-farming community around Ipoh. The announcement was followed up by massive fogging of pig-farming areas, and vaccination for people living or working in "high-risk" areas (2km-radius from any pig farm). But it soon became apparent that there were peculiarities about this outbreak. For one, our experience with JE which has been around in Malaysia for at least 45 years shows that it mainly affects the young and old, but rarely adults. In the case of Ipoh, over 80% of those who fell sick were adults. It is now known that the Nipah virus had been at work in the majority of deaths that number more than a hundred so far, including those from Negri Sembilan this year. Scientists from the US Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) who conducted retrospective testing on survivors and tissue or blood samples from those who died in Perak found that the outbreak is predominantly caused by a new Hendra-like virus of the Paramyxoviridae family.

Taking a rigid stand According to a paper titled Japanese Encephalitis Outbreak: The Kinta Experience, authored by Kinta district health officer Dr Marina Abdul Hamid and five others, 24 viral encephalitis cases were recorded in Ipoh between last September and mid-February. Only nine cases were confirmed as JE but the rest were included as JE on epidemiological grounds. But sources close to the Cabinet task force for JE reveal that at least nine from this batch of Ipoh cases were actually JE-negative. The question is: Why maintain the stand that it was JE when such a large percentage of victims were negative? Dr Henry Too, a swine expert from Universiti Putra Malaysia's Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, offers an insight. "For a disease that causes neurological disorders affecting people who are associated with pigs, JE was a logical presumptive diagnosis" during the early days of the outbreak, based on the fact that it was the only documented disease that affects the brain of those who work with pigs.

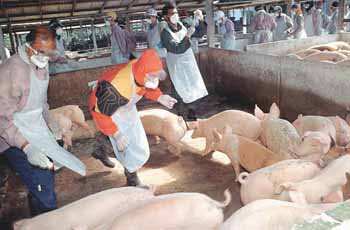

A respected figure in the medical community who is credited with discovering an adenovirus in the yet-to-be-resolved viral outbreak in Sarawak in 1997 (the so-called "coxsackie" episode), she noticed that the outbreak was concentrated heavily in pig-farming areas, when one would expect the mosquito-borne disease to spread over a wider section of the population. Despite the lack of conclusive evidence that it was JE, the authorities staged JE vaccination programmes for people living in high risk zones. Even the pigs were vaccinated. "People were falling ill and we had to do something," said Datuk Dr Tee Ah Sian, deputy director of the Disease Control Division at the Health Ministry, in an interview last week. Increasing doubts Till the end of last year, there was no report of any successful isolation of the JE virus from viral encephalitis patients, which is surprising considering Malaysia's familiarity with JE. Isolation of the virus from patients would have provided indisputable proof that the outbreak was really caused by JE. Scientists were bewildered by the disease's strange epidemiology, which has been described by the medical fraternity as being "totally unJE-like." Not only is the disease rarely seen in adults, the JE virus also rarely shows visible signs in a patient. The high rate of deaths also did not match JE mortality rates of 10% to 50%, usually affecting victims who are either very young or very old. But in the present outbreak, the patients and fatalities are mainly healthy adults. At a regional conference on JE held in Ipoh in February, Kinta district health officer Dr Marina herself had described as "puzzling" the fact that 80% of patients in Perak were adults. Stranger still is that residents in the same area but who do not have any close contact with pigs are not affected. The same goes for those who live under the same roof with the victims. Culex mosquitoes have not been demonstrated to be choosy about the humans they bite. And finally, even those who received the full course of JE vaccination also succumbed. In January, the virus appeared in the pig-farming communities in Negri Sembilan, first at Sikamat, then Kampung Sungai Nipah and Bukit Pelanduk. "When it came to Negri Sembilan, the JE diagnosis was no longer logical. There, pigs were dying with all sorts of strange clinical signs," said Universiti Putra Malaysia's Dr Too. Vets and farm owners reported that the sows were coughing, breathing with an open mouth (like a panting dog), shaking their heads in pain, biting one another and the pen bars, followed by a bout of fits before dying (and that with a copious discharge of blood-stained fluid from the nose)--all which are not typical of JE. In pigs, JE may cause sows to abort or produce stillborn piglets, but it does not cause deaths, and what more in such a dramatic manner. By then, the JE stand was already highly questionable, especially among those familiar with the epidemiological and clinical aspects of JE, said Dr Too.

'It's still JE' Nevertheless, the official stand was still maintained. At the Ipoh JE conference in February, the Health Ministry's Dr Tee stoutly defended the official diagnosis when questioned by experts in various fields ranging from animal health to epidemiology. But a few days later, Health Ministry deputy director-general (public health) Datuk Dr Aziz Mahmood conceded that only four out of the 25 deaths reported during the outbreak between October and March were caused by the JE virus. The breakthrough came in mid-March when Nipah was discovered with the help of the CDC. By then, not many were surprised when the discovery was announced. "We saw doctors at University Hospital running in and out excitedly, and we suspected that there was a new development. We cornered them and they admitted that they found something new," recalled farmer Chia Yu Bu who was there daily to visit his hospitalised co-workers. Still, even in announcing the discovery of Nipah, Health Ministry director-general Tan Sri Datuk Dr Abu Bakar Datuk Suleiman defended the JE diagnosis. "We are unsure of the role of the Hendra-like virus in the outbreak," he said. The official position back then was still one of "touching pigs is all right." The question that remains is why did the authorities go all out to contain JE in the later stages (especially in Negri Sembilan where about 80 people have died) when there was clearly a lack of evidence that the virus was involved in the fatalities? "On hindsight, everyone can be clever," said Dr Tee. "They (the critics) can say all sorts of things now that we have all the data. But four months ago, nobody told us that pigs and dogs were dying. We had no idea what was happening to the animals. "It is unfair to criticise us now as we had no idea that there was a new virus back then. We had to do something as people were falling ill and dying. Can you tell me of anything that we have failed to do?" Dr Thomas Kziazek, head of the CDC delegation to Malaysia to study the outbreak, alluded to possible errors during testing by the authorities. "There was too much reliance on what were thought by some people to be advanced science," he told Reuters. But to Universiti Malaysia Sarawak's Prof Cardosa, the issue was that the authorities only looked at trying to prove the epidemic was JE, and never really considered the alternatives, she said in an interview with the Asian Wall Street Journal last month. The AWSJ also reported that Prof Cardosa's offer to help analyse specimens from victims received no response from the health authorities. Prof Cardosa was also criticised for posting on ProMED (http://www.healthnet.org), an online forum on emerging diseases, her doubts over the official stand that it was the JE virus at work. Not long after the discovery of the new virus, the epidemic became known as the JE/Nipah outbreak. However, even this position was untenable to those familiar with the biochemical and physiological aspects of infections. A diagnosis of JE/Nipah is unacceptable when JE and Nipah are two distinct viruses, contends Prof Charles Calisher, a microbiologist at the Colorado State University in the United States on the ProMED online forum. He is among an international community of experts who are following developments of the outbreak in Malaysia. According to Dr Ksiazek, while there were some JE cases, it is clear to the CDC investigators that the predominant viral disease here is Nipah. "The JE 'business' is carried over from the early part. It's all behind us now. The numbers clearly show that it's Nipah," he said. From the 18 confirmed viral encephalitis patients who died between January 1997 and February this year, 12 of them were later tested Nipah - positive. Furthermore, out of 20 survivors, 18 were found to have Nipah antibodies. Looking back The insistence that the outbreak was JE has many implications. As Nipah is the one which was mainly responsible for the fatalities, it was a case of wasted JE vaccination on both pigs and humans, not to mention unnecessary panic. For the pigs, the same vaccination for JE can serve as a mechanism where the Nipah virus may be transferred from pig to pig (because the same hypodermic needle is used repeatedly). Fortunately, this risk was recognised a day after the vaccination exercise in Seremban began on March 23, and it was duly stopped. Still, this vaccination came to nought because the pigs were culled when Nipah came into the picture. Last week, the Veterinary Services Department confirmed that it was not giving up, but merely postponing vaccinating pigs for JE. In any case, vaccinating pigs for JE is certainly one of the strangest things to do, say swine experts, because pigs are the natural reservoir for the JE virus in the first place. Another consequence is that, believing the vector to be the Culex mosquito, many workers dutifully wore protective clothing, applied insect repellent, fogged their farms and made sure they left the farm before 6pm. But they failed to do one thing which could have been the best protection: refrain from touching the pigs. Indeed many lessons can be learnt from this outbreak. As Dr Jamal Hashim, an associate professor at Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia's Environmental Health Research Unit, says in an online medical discussion group: "Recognising failures is not to apportion blame. "In the case of the Nipah outbreak, even academicians like myself can accept partial blame for not highlighting enough the real threats of animal reservoirs and disrupted ecosystems to human health in our teaching and research. "But I'm willing to recognise this weakness and do my part to improve things. However, in order for us to improve our defences, we have to learn. "And in order to learn, we have to be open and transparent." At present, researches are trying to determine if the source of the Nipah virus is the bats of the Pteropus genus, commonly known as flying foxes. Also, there is a nationawide testing on other animals - such as horses, cats and dogs - to see how prevalent the virus is. But the greater task now is to ensure that pig farms are free from the virus. "Its not over until the last pig that might have the virus is gone,' said Dr Ksiazek.

|